By S. Mitra Kalita

S. Mitra Kalita is a veteran media executive, author of two books and was recently named News Live’s Assamese of the Year. She lives in New York City. Her ancestors and roots straddle the Brahmaputra's banks, Santipur in Guwahati and Sadiya in upper Assam. This writing appears in a book commemorating the 175th anniversary of media in Assam.

In 1983, the Assamese community gathered in a New Jersey church for the centennial death anniversary of Miles Bronson, the Baptist missionary who spent much of his life and career in India’s northeast. I was 7 years old.

I remember asking who Bronson was and was told he gave us our Assamese language. And I thought how curious that was, that the swirly script I could not read was “gifted” to my people by an outsider. Then I likely scampered off to play with my friends and eat the array of snacks and delicacies that our friends and family prepared for these meetings. Months later, a few families attending the annual Assam Convention held in Detroit made a pilgrimage to Bronson’s gravesite in Eaton Rapids, Michigan, where he died in 1883. The formality of the function, Bronson one day, Bihu the next, bhatmukhs and birthdays in between marking our seasons, was often besides the point; the main thing was to reconnect--with each other and our culture.

In recent years, I have learned the answer to my question -- just what did Miles Bronson do for the Assamese people? -- is more complicated. It turns out the Assamese script existed long before Bronson and other Baptist missionaries came along. Their contribution came in simplifying it, in the form of the first Assamese newspaper in 1846 and the first Assamese dictionary in 1867. More broadly, they fought to preserve Assamese as a language of instruction versus the Bengali (and English) imposed by the British. This context makes the celebration of 175 years of media in Assam, a media that today is thriving in written, digital and oral forms, quite remarkable.

The preservation of our language is politically fraught, often wielded as a weapon against outsiders who seemingly threaten the existence of Assamese culture and people. I wonder if perhaps an outsider like me offers another perspective on what Assamese might mean, and its ability to coexist with others in a world we hope remains connected and inclusive. The fact that Bronson was an outsider himself is, of course, the ultimate irony. It is perhaps also a necessary part of what enabled him to see something in the Assamese that they did not see in themselves -- or, more likely, did not have the power or privilege to assert under colonial rule.

I mentioned the backdrop of the Bronson centennial was a venue in New Jersey, the First Baptist Church on Union Avenue in Elizabeth. This church was an institution fading before our very eyes, year to year, with unmatched folding chairs and a piano in need of tuning. Immigrants like us rented the main hall on weekends and pumped it with life, youth, possibility, and, yes, polytheism. We had pitha and laru, of course, but Coke and Dunkin Donuts munchkins too. We played basketball and Bhupen Hazarika.

Years later, when my family and I lived in New Delhi, I excitedly planned a more “authentic” Bihu in Assam. My dream: a picturesque village scene, the sounds of birds chirping and cows mooing in between the pepa and husori geet signalling the dancers are near.

My reality: Around 1 o’clock in the morning, we were still awaiting main-act performances in the Chandmari section of Guwahati. With my husband and daughter, two cousins and a friend, I sat in a cracked red plastic chair sinking into the mud and watched a woman crooning into a microphone. She didn’t sound bad, but not great either. Nearby, young men smoked and I resisted the urge to ask them not to. It had taken us an hour to get here, an hour fighting traffic and other festival revellers. And that was after a day spent balancing relatives’ demands that I come visit all 50 of their homes scattered in all corners of Guwahati. (You have been there, am sure.) I realized I preferred my Bihu surrounded in the safety of beloved aunties and uncles who raised me, so far from their real homes. I missed that church in New Jersey.

I realized that for the transplant, home becomes but a nostalgic figment of the imagination, a make-believe place where you can pick and choose what to crave, to miss, to remember. It is ideal and utopian, even as the quest to recapture it impossible and dangerous.

I see similar trends with the purity of language and religion. The version many of us Assamese in America practice is an inclusive amalgamation, all thanks to a man named Brojen Bordoloi. When he died in 2018, it felt like losing my own father

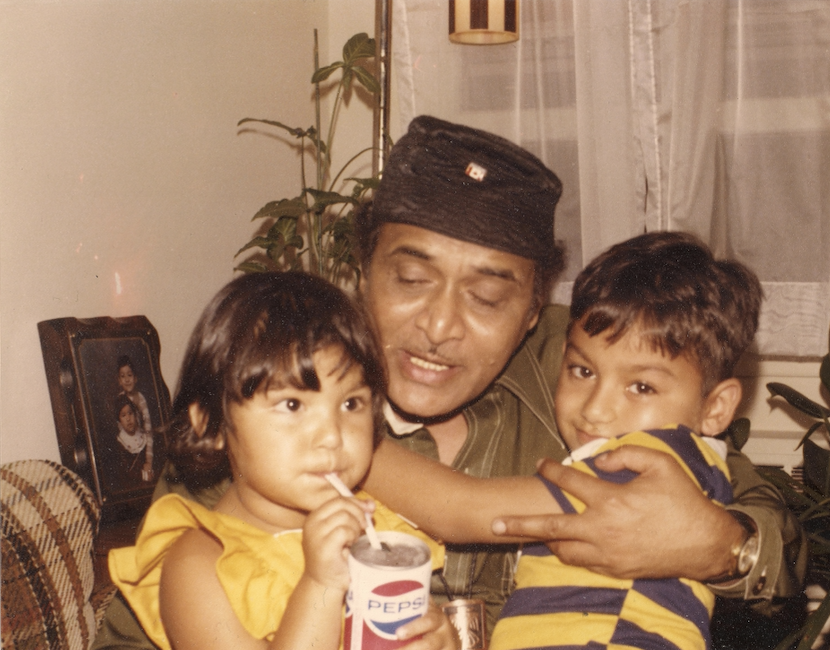

Both Bordoloi Uncle and my father Mohesh C. Kalita arrived in New York City in 1971, earning $1.85 working at a department store called Alexander’s and pushing a file cart in the district attorney’s office, respectively. Their path to America was paved by a Civil Rights Movement that changed immigration laws and allowed Indians like them to enter in larger numbers.

Meanwhile, remember that the Assam of the 1970s was a very different Assam from today. Just decades into the experiment of independence, Assam represented a certain secularist and socialist ideal.

This is an important backdrop to understanding how a tiny population of newcomers made their way in the U.S. Few Americans had even heard of India. How to explain Assam, a region literally cut off from the subcontinent? How to be an Assamese amid the sea of Punjabis, Gujaratis and much larger groups?

Brojen Bordoloi helped us define this. Virtually every weekend, he was called to living rooms and basements and essentially answered these questions -- in the form of naam-kirtan. Housewarmings. Baby showers (panchamrit). Pre-wedding ceremonies. Deaths. Death anniversaries. And on it went, for the vicissitudes of immigrants in a new land were many.

As people gathered together on the floor, his chants during naam were easy for us kids to copy. Often, he would employ call-and-response style: “Krishna Ram Narayan Gobindo Joy Joy,” he’d say. We’d repeat. He’d speed up. We’d speed up. It was like a game.

“Oh Hari,” he’d say. “Oh Ram,” we’d boom back.

I did not grow up eating vegetarian food, watching Bollywood movies or going to Hindu temples, as are the stereotypes of the Indian-American experience. But I did grow up with these sounds and rhythms and language. And they were the only formal cultural education I had in my life. That is to say, they were informal.

This became important as I grew up. As a member of the second generation, planning weddings and raising children and organizing housewarmings can feel rather complicated. These rites of passage force us to define ourselves, figure out what we stand for. My parents are not religious people; nor am I. Yet I longed for something that asserted some of my own roots as I lay them down here, in a land where I had none.

So in 2002, I called Bordoloi Uncle to bless the first apartment I bought, an apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens. He proudly came to perform a naam. I didn’t understand anything but it felt familiar, from all those years of other people’s services. It felt right.

Only years later, I would understand why, as I began to study Assamese culture closer for my book, “Suburban Sahibs: Three immigrant families and their passage from India to America,” I would write and then, eventually, when my family and I lived in India. Based on the teachings of the 15th-16th century saint-scholar Srimanta Sankardev, practices such as naam and bhaona are intentionally accessible and democratized forms of worship. In the caste hierarchy of Hinduism, they amounted to social-reform movements.

Indeed, what we preserve of our Assamese homeland in America has been a revolution, not unlike Bronson’s time fighting for the legitimacy of a language. On U.S. shores, men and women of all ages, castes and creeds partake in Assamese customs and traditions, thus asserting a unique identity from here and there. We fashion bhaona props out of baseball bats and duct tape, costumes out of old saris and princess tiaras and Halloween makeup. As it turns out, our homeland is not so much remembered as it is created.

As my daughters become the third generation with Assamese roots to make their way in America, I ponder what they will create. My husband, their father, is Punjabi but, like me, born and raised in America. Early in the pandemic, we all found ourselves living with my parents in their house in New Jersey. It was the longest time I stayed with them since I was a child. My mother tongue is clear -- my mother majored in Assamese at Cotton College and it is the language she is most comfortable in. My children’s mother tongue, inherited from me as their mother, is not; I was born in New York, raised speaking Assamese, learned English in school, lived in Puerto Rico and studied Spanish, went on to study Mandarin Chinese and Hindi more formally. I make my living with words. My eldest, age 16, inherited my love of languages -- and yet what is her mother tongue?

This past spring, as we tried to make the best of the pandemic, she asked me if she might learn Assamese from someone besides her mother and grandparents. Since that request, she and her younger sister, age 9, have weekly sessions with a tutor from Dibrugarh. They are learning the script and consulting a dictionary for words I never learned: like xompadok (secretary) and ghonsirika (sparrow). The evolution of their identity, the discovery of self, too, through learning of language fascinates me -- and gives me great hope that they will hang onto a connection to my parents’ homeland. Last weekend, the little one called out to her sister to get on the Zoom call with the tutor.

“Come uporot!” she laughed, blending words from here and there. “It’s time for Axomiya class.”

And so through the language, to the language, we cling.

-30-

Originally appeared in:

Write a comment ...