For the last few months of her life, my cousin Riku would WhatsApp me from India regularly. The first few messages were heavy, about where time went and how she didn't want hers to be so short. Then in recent days, she started asking what I ate for lunch or dinner. She wondered if my kids were in school or at home and how long their commute was. She wanted to know where I physically was in the house and if I had drank tea that day at all.

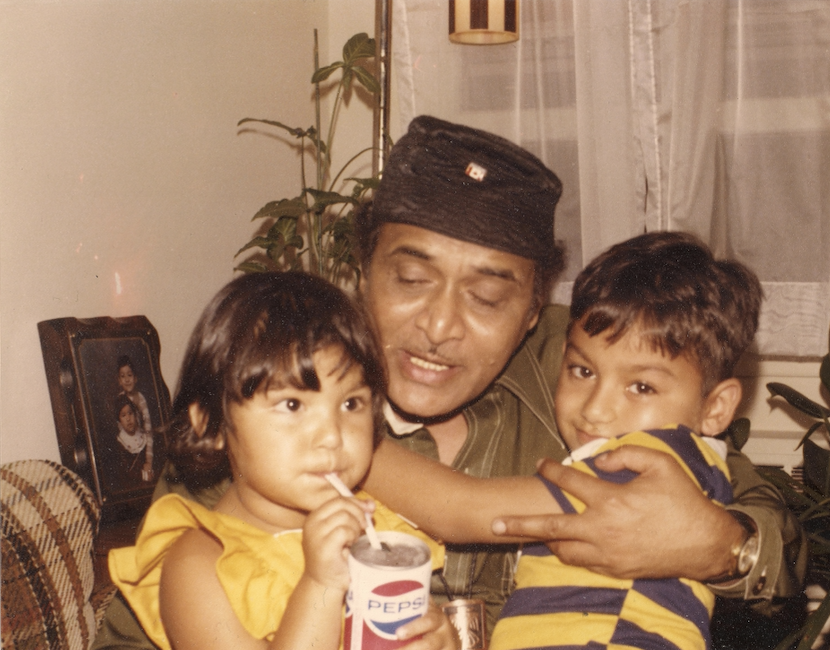

The banality of it all took me back decades to when we first met, a moment I actually don't recall. I was born in New York City and took my first trip to India as a toddler. Then we returned every three or four years. We would meet again and start with the same questions. Over and over, my dozens (literally) of aunts, uncles and cousins would ask about the minutiae of my day: What do you eat for breakfast? Do you walk or take the school bus? What time do you go to sleep? Do you eat a biscuit with your tea?

The conversations were rarely deep. Yet in between, they would sing to me. Scratch my back and mosquito bites. Fan me in the heat. And I eventually recognized these as acts of unconditional love, an intimacy and understanding among strangers-cum-relatives like none other I have ever experienced in my life.

It's been a week since Riku, daughter of my mother's brother, died of leukemia. When I look back on the grainy photos that captured our childhoods, I see my cousin-sister right next to me in so many, holding me close. As I hit my twenties, my relationship with my cousins and India deepened, partly thanks to frequent visits for work and weddings (so many) and a two-year stint I did in Delhi. We talked about boyfriends and husbands, compared the quirks of our parents, dissected modern India versus the squat toilets, episodes of "Air Hostess," card games and group chorus that occupied us pre-liberalization. The small talk got bigger.

Riku was the most beautiful among us, physically and metaphorically towering over us cousins on my maternal side of the family. For a brief time, she modeled. She fell in love and married. She opened a beauty parlor. During a period of the early 2000s, as all my cousins wed, she would help me throw henna parties and other Bollywood-inspired ideas I borrowed to liven up our austere Assamese weddings. She and her sisters are just a few years older than me but because their mother died when we were very young, they always felt light years ahead. They dressed me, dolled me up. We cousin-sisters formed a fleet, a gaggle and a bit of a revolution with our careers, love marriages and less conventional ways.

A few years ago, during Riku's brother's wedding, I happened to be in Bangalore for work so I flew to Assam to catch the rites. I remember her barking orders the entire time -- then quietly, tenderly asking her brother if he paid respects to their dead mother's photo before leaving for the bride's village.

After her diagnosis and a series of chemo treatments in Kolkata, interrupted by bandhs after the citizenship bill, then Covid's first and second waves, Riku and her husband researched clinical trials and experimental methods across the world to keep her alive. A few months ago, she called me crying. "I know the pain of not having a mother," she said. "I do not wish this for my children. I want to live. I want to fight however I have to."

In the meantime, India's descent into Covid chaos spiraled out of control. Clinical trials required arduous travel and uncertain expenses Riku wasn't sure she could endure. The irony of the world waking up to the need for broader vaccine distribution -- when healthcare inequities run deep across pretty much every single ailment and have for such a long time -- was not lost on us. I was torn on how to respond, how to be of comfort. I wanted to keep Riku positive and fighting, but I also knew the odds were against her. I hesitated to suggest she leave farewell videos or letters for her two girls, so instead I just told her to write down how she was feeling, either privately or via WhatsApp to me. Despite being born and raised in the U.S., my Assamese is fairly strong but words escaped me in these moments. So I resorted to English on WhatsApp: "I love you." It felt so cliche and inadequate.

Last week, my Friday, their Saturday, her sister sent me a WhatsApp informing me she was gone. Hours later, Riku's eldest daughter called me. I stuttered on what to say but chose the truth: "Your mother wanted more than anything to be alive for you."

That was indeed the gist of Riku's last sentimental message. In early May, she wrote me about her girls: "Mitra bahut besi sinta haise nijar babe nahai ehoter babe." Translation: "Mitra, I am very worried. Not for myself but for them."

Her next message, six hours later, is when I should have known things were turning. These final exchanges steered us back to normalcy, to the banter of our childhoods. So my final moments with my cousin-sister resemble my first. Riku told me she had just taken a bath and that it was raining in Guwahati. I told her it was raining in New York, too.

-30-

Write a comment ...