By S. Mitra Kalita

Each fist filled with salt, I circled my 17-year-old three times, trying to hold my breath under the mask. She had just tested positive for Covid-19 and I prioritized this ceremony somehow before the fetching of ginger ale, chicken soup, coconut water and more at-home tests. To conclude the ritual, she was supposed to spit on my hands.

Except I didn’t want her Covid saliva on me. So I told her to say “tu tu tu tu,” which was what my superstitious mom uttered if someone said nice things about us growing up. To ward off the evil eye. And here I was, fighting the same.

The Thursday night before, I’d been circling my teen, too, as she checked a web portal to see if she’d gotten into college, her first choice, early decision. “No,” she said quietly, incredulously. Because my daughter’s tone and posture help me assess if she’s happy or sad or anxious or hungry like an extension of myself, I knew. She was in.

People ask if I filmed the acceptance. I did not. I did not want to add any pressure to what has been pressure since she was 3 years old and interviewed for elite private nursery schools in New Delhi. Or when she was 4 and tried to take her doll into the gifted-and-talented test for New York City kindergarten. Or when she applied to a similar program in Los Angeles for middle school. And then of course the specialized exam to get into high school in New York City, after we moved back. She’d been measured up plenty.

I grew emotional a few of those times but not like this. Later, my daughter would tell her younger sister, “When I got in, Mama cried like someone just died.”

So no, I didn’t film it.

The next few days brought celebration: late-night dessert in Flushing, cards and sweet messages at school and on Instagram, cheesecake with her grandparents. On Sunday morning, when her sister came down with a runny nose and cough, our response was rote: Time for another Covid test. We waited in line at our go-to van in front of a Corona church for about a half-hour, and received results in about the same time: negative.

It wasn’t until the next day that her positive result—and hers alone was positive—changed everything. Friends texted advice on how to quarantine and deal with Covid, of course. But in our circles, there was speculation beyond the diagnosis. “It’s too much good news,” said one family member. “That’s why this happened.” Our babysitter echoed that: “This is nazar. Someone is jealous. I will pray.” My husband said maybe it happened because we didn’t worship much at temple besides the upma and onion rava masala they sell at the canteen.

This concept of nazar is shared across South Asian and Middle Eastern cultures; bad luck falls upon those who’ve had a string of good luck, their fortunes ranging from being attractive to receiving compliments to … getting into college. There are myriad ways to combat nazar, from beads and amulets, to a black mark on the side of a baby’s head to the phrase “tu tu tu tu” as though you are about to spit on the object of everyone’s affection and attention.

It was my neighbor who sent me the fistfuls-of-salt idea. In the face of such powerlessness, it seemed like something to do.

After my teen's unenthusiastic "tu tu tu tu," I washed the salt down the drain of the bathroom. Then I shut her door, which is pretty much how it stayed for the next week. We left trays of soup, vitamin gummies, oranges and meals on a mura in the hallway.

What a weird week it was. I had already written and printed our holiday letter and thought about updating it, just in case all the “we’re doing great in a pandemic!” cheer prompted more nazar. "Christmas letters are for assholes," the mother in “Jagged Little Pill” says in one scene that felt written just for me when I saw it on Broadway last month. She goes on to write a more vulnerable and honest dispatch, including news of drug abuse and an eventual relapse.

I wondered if I should recast our family’s version: the fights between our kids, the despair we feel every time one of our parents is in the hospital, how much weight we gained, lost, gained again. Then I looked at my to-do list for the remainder of the week. No time. Just gotta let everyone think we’re really doing great!

An unexpected thing happened shortly after my daughter got Covid. Everybody else did, too. Surely so many evil eyes could not have been cast on all of us?

It was a rhetorical question but I found a semblance of an answer on Facebook. Somebody posted this grainy 1980s video as a comment on a friend’s post: “When bad things happen to good people,” a speech by rabbi Harold Kushner.

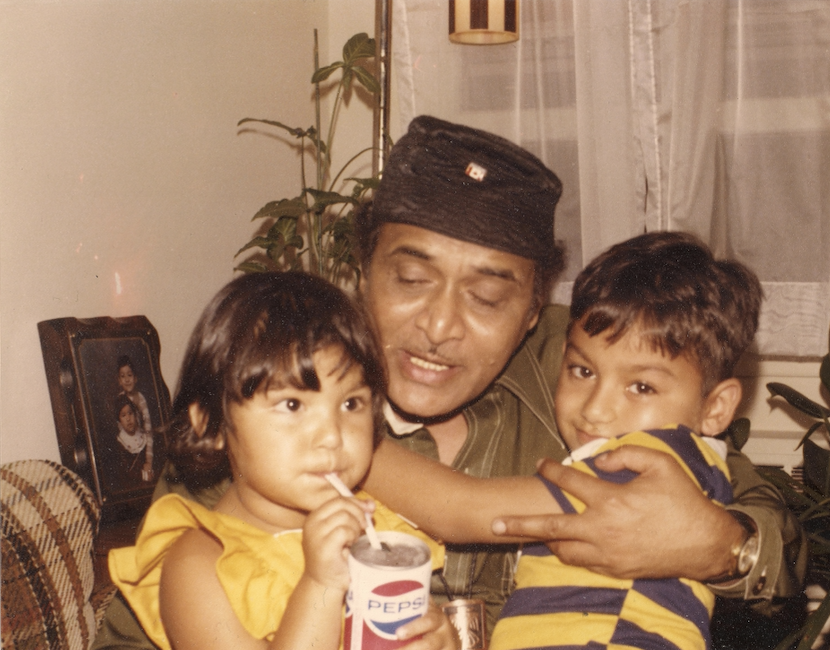

I suddenly remembered my father not only had this book but quoted from it often. Before two strokes that limited his mobility and speech in recent years, Papa was the type to rush to someone’s house if tragedy struck: lost jobs, death, cancer. Intellectual yet aloof, he couldn’t help but cite random advice as people wept to him. Instead of hugs, my stoic and pragmatic father shared wisdom from Rabbi Kushner, Richard Feynman, Buddha, Bertrand Russell, Morrie Schwartz, among so many others.

Last night, as my daughter’s quarantine ended and she prepared to exit her room at last, I decided to watch the hour-long speech by the rabbi. I felt like he was talking to the version of me clenching those fistfuls of salt, struggling for control and answers amid ups and downs. According to Kushner, we blame something or someone in bad times. But Kushner reminds us he didn’t title his book “Why bad things happen to good people.” It’s “When bad things happen to good people” to reflect the inevitability of it all.

The lightbulb that went off in my head is similar to that moment after my wedding 17½ years ago and, a few months later, the birth of my daughter. Until then, life had been in fast-forward motion to get to the destination: grad school, job, boyfriend, better job, husband, better job, pregnancy. Having a child prompted all sorts of unsolicited advice on “enjoying the journey.”

Our reaction to bad news is “You must have done something to deserve this,” says Kushner. He addresses disease head on and assures us that the “laws of nature can’t tell the difference between a good person and a bad person.” A doctor, a burglar, a bad person, a good person, “germs they don’t know the difference.” Neither does Covid, I suspect the rabbi would agree, in these modern, uncertain times.

What matters is what you do after being dealt a blow, big or small. Do you take the pain or anger and turn it into something positive? Do you try to help people based on your own experience?

We’ve been through so many of these Covid surges. Last week was our family’s turn. It will likely come again, not a matter of if, more a matter of when.

My daughter returned to school this morning, practically floating out of the house to resume senior year and rejoin society, after a relatively mild bout with Covid. A gift. We’ve been handed so many this month.

Tu tu tu tu.

-30-

Write a comment ...